In this article, we examine infant suction patterns, emphasizing the importance of peak vacuum and comfort in maximizing milk removal and providing practical implications for breast pump usage.

Infant sucking: two key rhythms and the role of vacuum

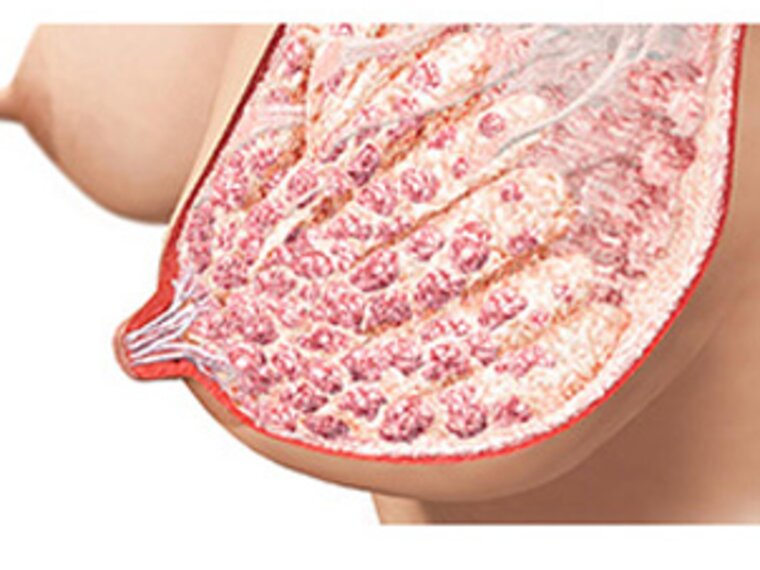

In breastfeeding, a suction pattern refers to the rhythmic sucking behavior of an infant during feeding. It encompasses the frequency, strength, and duration of suck bursts and pauses (short breaks between bursts). In established lactation, infants exhibit two distinct suction rhythms essential for successful feeding1-4:

- Non-nutritive sucking: characterized by fast (>100 sucks per minute), stimulatory suckling, this rhythm primarily serves to trigger milk ejection at the beginning of a feeding session.

- Nutritive sucking: This slower (~60 sucks per minute), more deliberate rhythm is responsible for extracting milk from the breast.

The connection between vacuum and milk removal is well established through research on breastfeeding infants.5,6 Vacuum plays an essential role in milk removal during nutritive sucking.7

When feeding at the breast babies intuitively go through the following key steps in a nutritive suck cycle:

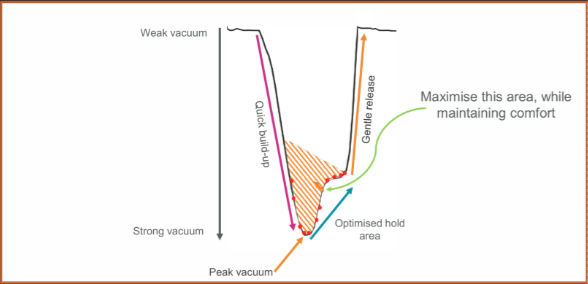

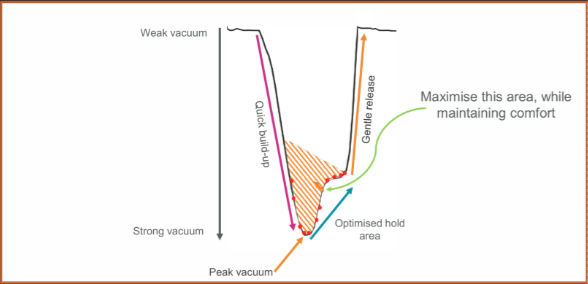

1. Quick build-up of vacuum, 2. Peak vacuum, 3. Comfortable Hold and 4. Gentle release of the vacuum.8,9

Key elements of a nutritive suck cycle – contributing to comfortable and effective milk removal

Optimizing pumping: the significance of peak vacuum and comfort

Studies on the pump nutritive suction curve have revealed that peak vacuum plays a key role in milk output during nutritive-like cycles.10 Higher peak vacuums have been associated with increased milk removal efficiency for both infants and pumps7,10. Conversely, for non-nutritive-like cycles, peak vacuum has not been associated with triggering milk ejection faster.8

Beyond peak vacuum, the duration of the Hold Area within the suction cycle is also vital. An optimized Hold Area is long enough to be effective in milk removal but not too long to cause discomfort to the mother.9

Furthermore, when mothers pump at their Maximum Comfort Vacuum (MCV), compared to weaker vacuum levels, a greater volume of available milk is removed, resulting in better breast drainage.10 This highlights the direct link between a mother’s comfort and the efficacy of milk expression.

Practical implications for mothers and healthcare professionals

These research findings have significant implications for mothers who use a pump.

At the beginning of a pumping session, when aiming to trigger milk ejection, mothers do not need to strive for high vacuum levels8. The vacuum strength that infants apply to trigger milk ejection is typically lower.4

As soon as milk begins to flow, the pump should be switched to extraction (nutritive-like) mode, and mothers are recommended to increase the vacuum strength until they reach their Maximum Comfort Vacuum (MCV). This is the highest comfortable vacuum level, optimizing milk removal efficiency.10

It is crucial to emphasize that the MCV is highly individual and can vary significantly among mothers (ranging from -98 to -270 mmHg in established lactation.10 Moreover, keep in mind a mother's preferred MCV level can change over time, typically increasing over the first month postpartum and stabilizing in established lactation.

Key advice for mothers:

- The appropriate pump setting is the highest vacuum level that remains comfortable for the mother.

- Advise mothers to increase the vacuum setting in the "milk extraction" mode to their maximum comfortable vacuum.

- Encourage mothers to move beyond default pump settings and actively experiment to find their individual comfortable and effective vacuum levels, especially if their pump has a ‘memory function’.

- Pump power vs. effectiveness: When selecting a pump, emphasize that more 'powerful' doesn't always mean more effective. Research on pump curve shape identifies combinations of vacuum and cycle patterns that yield both comfort and effectiveness.9

Technological advancements in breast pumps

Breast pumps have incorporated these scientific results into their technologies.

For instance, Symphony®, from the #1 brand in hospitals (based on Distribution in maternity wards and NICUs), has successfully mimicked infant sucking behavior with the clinically proven Symphony® pumping pattern to achieve the best balance of comfort and efficiency. Its Initiation Technology targets the first days before milk ‘comes in’11,12 , while the 2-Phase technology is for milk removal during established breastfeeding.8,10,13

Innovative technologies, such as FluidFeel Technology™, further enhance the pumping experience through a unique interplay of features. .This technology creates an environment around the nipple similar to breastfeeding, allowing for gentle pumping even at high vacuum levels. FluidFeel Technology™ promotes a constant seal with continuous vacuum, minimizes back-and-forth nipple movement, and creates a warm, moist environment in the tunnel with almost no air. Advanced sensors continuously monitor and automatically respond to milk flow patterns, ensuring stable vacuum levels throughout each pumping session. Additionally, for the utmost comfort of mothers, the system operates silently and thanks to its compact size, is well-suited for inBra pumps.