A question of timing

The first two weeks after birth will decide if a good milk supply can be built and maintained long-term, but it is an even shorter window – the first 72 hours – that is available to successfully initiate lactation. The reason for this critical window is a shift in mammary gland development which is guided by hormonal (endocrine) control, with quite dramatical changes in the first days after birth. During pregnancy, milk secretion begins around 20 weeks, but high progesterone levels suppress full milk production until after birth, when hormonal shifts trigger secretory activation.16,17

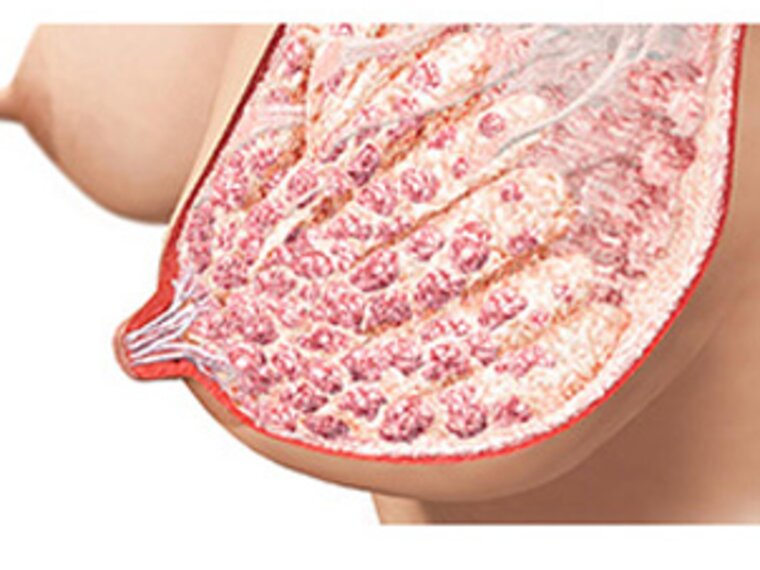

Following birth, there is a rapid drop in progesterone levels, facilitated by the delivery of the placenta. Once progesterone levels fall, prolactin is free to promote secretory activation. It supports the closure of the lactocyte tight-junctions sealing the alveoli, so milk stays inside and doesn’t leak into surrounding tissue. Each suckling event, each regular stimulation of the nipple and areola through breastfeeding or pumping, sends the message to the mother’s brain to 'produce prolactin'.17

Oxytocin also comes into play here. After stimulating contractions during labour, it remains high for the first days after birth to prime the ensuing breastfeeding interaction. Oxytocin pulses occur during suckling and are required for the release of available milk throughout lactation (milk ejections).

Consequently, during this time, regular stimulation and effective milk removal is essential to activate the mother's milk production. Risk factors – whether hormonal, glandular, or related to poor milk removal because the infant is experiencing sucking difficulties – can disrupt this process and must be proactively identified and managed. This is why supporting and preparing mothers-to-be during pregnancy – by identifying potential risk factors for lactation and developing breastfeeding plans to achieve timely secretory activation – is the prerequisite for long-term breastfeeding succes.

Breastfeeding support must begin during pregnancy

Prof. Viktoria Vivilaki, President of the European Midwives Association, is a strong supporter of the roundtable discussions issuing the latest call for proactive lactation support. Her expectations for the future are clear.

Why is proactive lactation support so important?

Proactive lactation management plays an essential role in ensuring breastfeeding success. Early initiation and strategic support in birth centres and maternity clinics significantly impact long-term milk production and maternal confidence. Given the declining breastfeeding rates in some European countries, an evidence-based framework for enhancing perinatal care practices is crucial.

When should support begin?

Breastfeeding support must begin during pregnancy and immediately at birth. It should be an integrated part of perinatal care, not an optional service. It is important to set realistic expectations and address concerns. The recommendations we laid out emphasize structured, proactive guidance to prevent early breastfeeding challenges, especially in mothers at risk of delayed lactogenesis. This approach reduces unnecessary supplementation and increases breastfeeding success.

How should midwives implement the recommendations in daily practice?

Midwives are key players in breastfeeding support. Implementation involves routine lactation education to ensure standardized, evidence-based practices, as well as hands-on support in the first hours postnatally to ensure optimal latch and positioning. We also need to ensure close follow-up beyond hospital discharge by community midwives. Collaboration between professionals is key here. We need to work together to identify mothers at risk early on, to ensure immediate and continuous support is guaranteed.