Breast shield design and fit play a crucial role in enhancing milk removal, comfort, and the overall pumping experience for mothers.1–5 While it may seem like a small part of the breast pump, the shield directly interacts with delicate breast tissue making its design and fit especially important.

Understanding breast anatomy and shield interaction

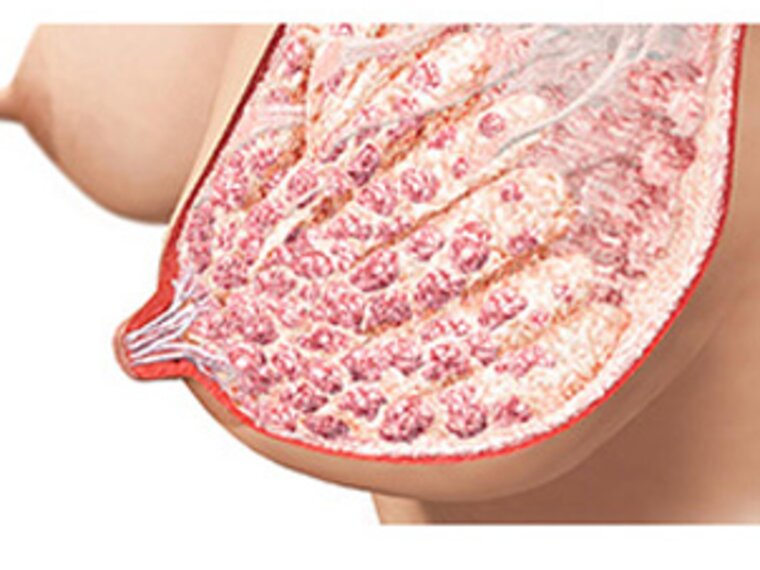

The lactating breast is a complex structure. Milk ducts lie just beneath the skin6,7 and are highly compressible, meaning that any pressure from pump parts against the breast can impact milk flow.1 That’s why breast shields must be designed with care: they should avoid compressing the breast, support gentle elongation and radial expansion of the nipple,8 and limit the amount of areola entering the tunnel.

A breast shield consists of two main parts:

- The flange, which contacts the breast

- The tunnel, which accommodates the nipple

The flange design makes a significant impact to pumping success and lactation outcomes.1 Research from Medela has shown that a flange with a wider opening angle 105° compared to the traditional 90° can improve comfort, increase milk volume expressed, and enhance breast drainage.1 Breast shields come in various tunnel diameters to suit different nipple sizes. Importantly, breast size does not correlate with nipple diameter a mother with large breasts may need a small shield, and vice versa.

While standard shield sizes have been shown across research to offer both comfort and performance on average for mothers,1,9–13 an incorrect fit can lead to:

- Reduced milk flow due to duct compression7,14

- Discomfort from excess areola entering the tunnel (ideally limited to approximately 3mm)15,16)

- Friction and breast tissue trauma 3,14,17

Practical tips for finding the right fit

Step 1: Measure the nipple

- Measure before pumping or feeding4

- Measure each breast separately

- Measure the widest part of the nipple, taking into account any asymmetry

o recent data shows that 50% of nipples are wider horizontally than vertically18 - Re-measure over time

o nipple measurements have been shown to be different from week to week,18 and in the early postpartum days any nipple and areola edema can impact sizing.19

A good starting point is to add 2–4 mm to the measured nipple diameter to allow room for nipple expansion and movement during pumping4,12,13,18 While the degree of expansion varies among mothers, published data indicates an average increase of 2─3 mm during pumping.4,15,12

Step 2: Test during a pumping session

Nipple measurement is just one part of the puzzle. Other factors include pumping frequency, breast tissue sensitivity, elasticity,4 milk duct and intra-glandular fat distribution,6,15 the tendency of the tissue to swell4,12,15 and maternal comfort.4,5 Observing nipple and areola movement during the first 5 minutes of pumping at the mother’s maximum comfortable vacuum9 is a key sizing step. Look for:

- Free movement of the nipple

- Limited areola entering the tunnel

- Areola colour changes e.g. blanching or increased erythema

Consult with the mother as to whether it is comfortable or painful and review sizing again after a few days. Tailored approaches are a true conversation between the lactation professional and the mother, and positive outcomes in both comfort and milk output have been reported with individualized approaches.4,5

The role of vacuum

Using the maximum comfortable vacuum is one of the most effective ways to optimize pumping.9 It helps remove more milk and improves breast drainage. Mothers should be encouraged to:

1. Increase vacuum setting until the first moment of discomfort is felt.

2. Then reduce to the highest comfortable level.

Interestingly, shield size can influence vacuum tolerance. Both too large and too small shields have been associated with lower maximum comfort vacuum levels.13,15 Since vacuum tolerance can change over time, regular reassessment is recommended to ensure the fitted shield allows the mother to express at her highest tolerable vacuum to enable effective milk removal.9

Special considerations for exclusive pumpers

For mothers who pump frequently, such as those with babies in the NICU ongoing evaluation of shield fit and comfort is essential, while minimizing complexity and stress.20 For these mothers, pumping needs to feel comfortable and sustainable, so follow-ups including sizing checks, are key to maintaining comfort and output. There remains the need for further research into how shield sizing needs may change over the course of establishing lactation,21 and while going through phases of postpartum edema19 or engorgement.

Summary

Breast shield sizing is a powerful tool in supporting a mother’s pumping journey. The right fit balances comfort, performance, and safety. Starting with a shield 2–4 mm larger than the nipple diameter is a simple, safe and effective approach for most mothers. For more personalized support, working with a lactation consultant can help tailor the fit to individual anatomy and comfort needs.